Debt Recovery – Small Claims

In this information sheet:

Introduction – letter of demand

This information sheet assumes that the contracts under which money is owed are legally enforceable, and that the debts are not subject to the National Consumer Credit Protection Act 2009 (Cth) or the National Credit Code If you are unsure, please contact Arts Law on (02) 9356 2566 or toll-free on 1800 221 457.

When chasing payment for goods or services, the first step is generally to send a letter of demand to the other party telling them of the dispute and the money outstanding, and giving them a defined period within which to settle the matter or else face legal action.

When sending a letter of demand, you should be careful not to:

- harass the debtor – they have the right to complain about this behaviour to particular government agencies and the police; or

- send a letter which is designed to look like a court document because this is illegal.

A guideline on acceptable and unacceptable debt collection practices is published by the Australian Securities & Investment Commission (ASIC) as ASIC Regulatory Guide 96 – Debt collection guideline: for collectors and creditors. It is available at the ASIC website.

For assistance with drafting a letter of demand see Arts Law’s information sheet on Debt recovery Letter of Demand.

Response to letter of demand

In response to a letter of demand, a debtor may:

- pay the full amount owing;

- show that no money is owed;

- negotiate a compromise, for example, payment by instalments or part payment; or

- ignore the letter or respond to it in a way that is unsatisfactory to the creditor.

If you agree to a compromise with the debtor, make sure that it is in writing, or is confirmed in writing if agreed verbally, to avoid later disputes. You can seek the assistance of Arts Law regarding the form and terms of that agreement, including any release you are asked to provide the debtor in return for part payment.

You may consider writing off the debt – if, for example, the debtor’s response to your letter of demand is unsatisfactory; the size of the debt is so small that you decide that it is not worth pursuing further or because the debtor has asked you to do this and you have agreed.

If the debt is relatively small – say under $2,000 – many people decide to write off the debt because of the perception that it is too difficult and expensive to pursue, especially if lawyers are retained.

If you decide to write the debt off, you may be able to claim an income tax deduction or a Goods and Services Tax (GST) adjustment so that you do not pay income tax or GST on the amount that you do not recover from the debtor. See the ‘Taxation implications of bad debts’ section of this information sheet.

Small Claims debt recovery action

All State and Territory courts in Australia offer a small claims division of their local court or tribunal that provides a simple debt recovery procedure. Advantages are that the process is relatively informal, and that costs awarded against an unsuccessful party are limited.

So, what is a “small claim”? A small claim is a claim:

- in respect of money, goods purchased or delivered, labour or a combination of these; and

- an amount up to $25,000 depending on the State or Territory in which the legal action is conducted.

You are encouraged to represent yourself in a small claim and the circumstances when you can be legally represented may be limited.

If the debt is over the limit provided for in the relevant small claims division, you can still bring an action against the debtor, but you will probably need legal representation or at least legal advice.

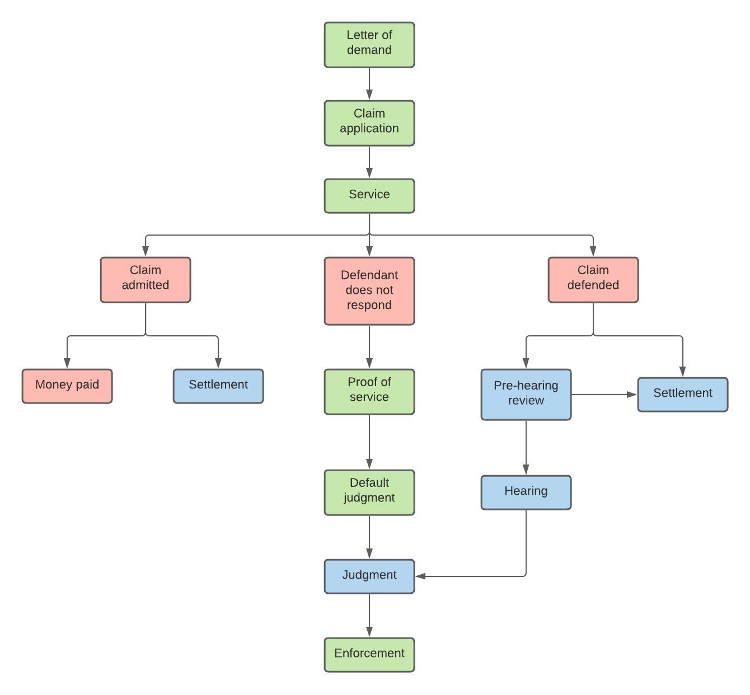

General process:

To sue or not to sue…

Things to think about when deciding whether to commence a debt recovery action and when you should do this, include:

- Can the debtor pay? If the debtor has a number of creditors seeking payment of debts and is basically bankrupt or insolvent (i.e. unable to pay their debts as they fall due) it may not be worth pursuing legal action. If, after a company search, you find that a company is in the hands of a receiver or liquidator, contact that person directly.

- Is there a genuine dispute over the facts and is the evidence to support your claim strong enough? It is important to consider the strength of the evidence that you have to support the specific legal claim you are making. If your claim is unsuccessful and the other party retains a solicitor to represent them (this is not common in small claims), the other party will usually apply for a legal costs order against you.

- Will the time and cost involved in going to court outweigh any additional money that you might receive from a judgment as compared to a settlement offer? In most matters involving relatively small sums it is generally worth the effort to settle a matter out of court as court proceedings take time and cost money. Again, if you do reach an agreement with a debtor, make sure that the agreement is in (or is at least confirmed in) writing, to avoid later disputes.

- Is there a time limit on bringing your claim and when will it expire? The time limit on bringing a debt recovery action is generally 6 years from the date the debt first arose, except for in the NT where it is 3 years. Limitation periods can start again, though, in certain circumstances, such as when a debt is confirmed by a debtor signing a contract that states the money owed to the creditor. You may need help from a lawyer to work out the relevant time limits, if they are an issue.

Who can I sue?

A small claims action can be brought against a person (sole trader), a group of people (partnership) or a corporate entity (company, incorporated association or cooperative). Generally, the court filing fees are more expensive for claims against a corporate entity.

It is important that you identify the specific entity that owes you the debt so that you can bring your claim against the appropriate person or corporate entity. If you name the wrong entity in your claim, any judgment you receive may be unenforceable. If the debt that you want to enforce arises under a contract, check the details of the contract for the name of the other party. If you had a verbal agreement with another person, consider whether they were dealing with you in their individual capacity or as a representative of a business.

If the debtor is trading under a business name you will need to do a business name search to identify the owner of the business. This search can be done using the ASIC Organisation and Business Names register (formerly the National Names Index), which can be accessed free via the ASIC website.

The debtor has to be identified in the Defendant or Respondent details of your claim form (often referred to as the Statement of Claim) as follows: “Respondent – Glen X of 99 Surreal Crescent, O’Connor, ACT”. Where the debtor is using a business name, you will need to add “…trading as (or “t/a”) [insert name eg Fantasy Dressers]” at the end.

As identified above, you will also need to specify the correct address for the debtor. If the debtor is a company – for example, Fantasy Dressers Pty Ltd – any business documents (such as invoices and business letters) should have its nine-digit Australian Company Number (ACN) after the company name. A company search, using this ACN, should be conducted through ASIC to identify the address of the registered office at which to serve the Statement of Claim and to ensure that the company is not in liquidation (you will have to pay a fee to ASIC to complete a registered office address search. See the ASIC website for more information).

If the person whom you intend to sue is an individual under the age of 18 you will need to obtain further advice from a lawyer or from the court staff before proceeding.

Taxation implications of bad debts

You may be able to claim an income tax deduction or a Goods and Services Tax (GST) adjustment in respect of a bad debt.

In order to claim a tax deduction for a bad debt deduction under section 25-35 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (Cth), the following minimum requirements must be met:

- the bad debt must be written off in writing;

- the bad debt must be written off in your financial accounts;

- the bad debt must be written off before the end of the financial year in which you are seeking to claim the tax deduction;

- you must retain written records relating to the writing off of the bad debt and to the claiming of the tax deduction; and

- if the tax deduction is claimed by a company, the company must meet the conditions in section 165-123 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (Cth) (about maintaining the same owners) OR meet the condition in section 165-126 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (Cth) (about satisfying the ‘same business test’).

For more information about income tax deductions for bad debts, see the Australian Taxation Office ‘Taxation Ruling TR 92/18’ and/or seek advice from a taxation professional.

If you account for GST on an accrual basis, you may be able to claim a GST adjustment if you decide to write the debt off, or if the debt has been overdue for 12 months or more. If you have reported the GST in respect of the bad debt but have not received all or part of that GST from the debtor, you may have reported too much GST. You may be able to claim a decreasing adjustment on your Business Activity Statement (BAS) in the tax period in which the debt is written off, or if it has not been written off, in the tax period in which you become aware that the debt has been overdue for 12 months or more.

For more information about GST adjustments for bad debts, see the Australian Taxation Office ‘Goods and Services Tax Ruling GSTR 2000/2’ and/or seek advice from a taxation professional.

More information

Find out more information about small claims in your state or territory:

- Australian Capital Territory

- New South Wales

- Northern Territory

- Queensland

- South Australia

- Tasmania

- Victoria

- Western Australia

For a full list of helpful contacts in your state or territory download the PDF.

Arts Law cannot represent you at these proceedings and cannot draft your documents for the proceedings, but we can advise you about your rights in an arts related matter both before and during any legal action you pursue. If the debt is over the limit for a small claim and you need legal representation, Arts Law can assist with referrals to an appropriate solicitor.

Australian Capital Territory

In the ACT, a small claim is a claim:

- for $25,000 or less; and

- where the debtor is resident in the ACT or a material part of the subject matter of the claim has arisen in the ACT.

Section 266A of the Magistrates Court Act 1930 (ACT) prevents the Magistrates Court from dealing with civil disputes involving less than $25,000. Disputes involving less than $25,000 fall within the jurisdiction of the ACT Civil and Administrative Tribunal (ACAT).

If the claim is over $25,000, you can still bring an action against the debtor, but you will probably need legal representation or at least legal advice. Also, such claims must be dealt with by a superior court (the Magistrates Court for claims up to $250,000 and the Supreme Court for larger claims) unless the parties both agree that it can be dealt with by ACAT.

The limitation period for debt or contract issues is 6 years after the action first accrues. The cause of action usually accrues when the debt becomes due or when the contract is not fulfilled. If you are outside the 6-year period you may still be able to bring a claim, but the other party can raise the expiration of the limitation period as a defence and ACAT (or the court) may deny your claim.

Small claims procedure

When can I use the ACAT?

The ACAT may be used for claims of up to $25,000. You may consider abandoning the excess over $25,000 in order to take advantage of the ACAT procedure which is quicker and cheaper. Claims of more than $25,000 must be brought in the Magistrates Court, unless the parties agree to use ACAT.

How do I make a small claim?

ACAT has a useful Guide to Applicants on its website (https://www.acat.act.gov.au/case-types/civil-disputes) which contains the forms you will need. Complete the Civil Dispute Application form either online or in hard copy and pay the filing fee. If you decide to apply with the hard copy, make sure to file two copies with ACAT. Remember to include on the claim form accurate details of the name and address of yourself (‘Applicant’) and the debtor (“Respondent”). If you are making an application on behalf of a company, you will also need to lodge an Authority to Act for a Corporation form. Unless informed at the time of lodgement that you want to serve the application yourself, ACAT will serve a copy of the Civil Dispute Application form on the Respondent by pre-paid post.

If you choose to serve the Civil Dispute Application form on the Respondent yourself, you must complete an Affidavit of Service within 72 hours and file it at ACAT. The Affidavit of Service is proof that the Respondent has been served with the Civil Dispute Application.

If you are claiming a sum of money, you may include a claim for interest on that amount.

How much will it cost?

There is a small lodgement fee for filing your claim. For further information on lodgement fees you can visit the ACAT website here: https://www.acat.act.gov.au/fees-and-forms/acat-fees

A hearing fee is charged if the matter goes to a hearing which lasts longer than one day – although this is not usually the case for small claims.

What happens next?

Within 21 days from the date on which the claim is served*, the Respondent must:

(a) pay you the full amount – in which case you need to notify ACAT that the debt has been paid; or

(b) file a Response with ACAT stating that the debt is disputed either in full or in part or admitting the debt and making a proposal for payment; or

(c) contact you to try and reach a settlement agreement – if you do reach an agreement, ACAT must be notified in writing.

If the Respondent fails to do any of these things within the 21 (or 25) day period, the Applicant may file an ‘Application for Default Judgment – Civil Dispute’ form requesting ACAT to enter a judgment against the Respondent. If the Defendant does not have a good reason for failing to file a Response, a default judgment application allows ACAT to make a decision in the Plaintiff’s favour without going through the full trial process. This is only possible where the Civil Dispute Application Form sets out the Plaintiff’s case in enough detail, which is you should ensure you complete it as best you can.

*If the claim has been posted to the Respondent or the Respondent is located outside the ACT, you must allow an extra 4 days.

Can I settle before the hearing?

Yes. If you do reach an agreement, ACAT must be notified in writing.

If the Respondent files a Response, ACAT will usually arrange an informal conference where a Tribunal officer will encourage and assist the parties to settle the dispute. If an agreement is not reached in the conference, the matter will be heard by ACAT.

What happens at the hearing?

The parties will be notified of the hearing date. You may wish to be represented by a lawyer at the hearing, although many people choose not to do so as solicitors’ costs are not recoverable even if you are successful. It is important for both the Applicant and the Respondent to have all evidence prepared and available to prove their case. After listening first to the Applicant’s case and then to the Respondent’s case, the Member will make orders which are legally binding on the parties.

Costs

Generally, each party to the proceedings must pay their own costs. While the successful party can’t recover all of their costs, the ACAT does, however, have discretion to order an unsuccessful Respondent to reimburse the Applicant for the cost of the filing fee. The Tribunal also has discretion where one party causes unreasonable delay or obstruction to order that party to reimburse the other party for the reasonable costs arising from the delay or obstruction.

Enforcement

If you are successful and the Respondent does not pay you, there are a number of methods of enforcement. ACAT’s order is treated as an order filed in the Magistrates Court and can be enforced under the rules of that Court. The Court may order the sheriff or bailiff to seize and sell the judgment debtor’s property to satisfy the debt owed to you or make an order for regular payments ‘attaching’ to the wages or earnings of the Respondent until you are paid. If you are in this position, we recommend that you seek advice from Arts Law.

Appeals

An unsuccessful party can appeal a decision by ACAT. The appeal must be lodged within 28 days of the decision (although ACAT can extend the time).

New South Wales

In NSW, the Local Court deals with debt recovery claims up to the value of $100,000. If the amount of money that is owed exceeds $100,000 you will be required to commence action in either the District Court or Supreme Court of NSW.

The local court has two divisions to determine civil cases; the Small Claims Division hears claims up to $20,000 and the General Division hears claims over $20,000 (up to $100,000).

The limitation period for debt or contract issues is 6 years running from the date on which the cause of action first accrues. The cause of action usually accrues when the debt becomes due or when the contract is not fulfilled. If you are outside the 6-year period you may still be able to bring a claim, but the other party can raise the expiration of the limitation period as a defence and the Court may deny your claim.

Small claims procedure

In NSW, you may use the Small Claims Division of the Local Court for claims less than $20,000. However, its General Division can hear claims between $20,000 and $100,000. Proceedings in the Small Claims Division are less formal meaning that there are usually no witnesses or lawyers unless the Court allows it. There is also a limited right to appeal. Claims in the General Division are more formal, and appeals can be made to the Supreme Court on a question of law.

How do I make a small claim?

To lodge a claim, including a small claim, you need to file a document with the court which is referred to as an ‘originating process’. A Statement of Claim is a type of originating process document which can be lodged with the Local Court to commence proceedings.

The Statement of Claim and other Local Court forms are available online on the Local Court website here: https://www.localcourt.nsw.gov.au/ or on the Justice NSW website here: http://www.ucprforms.justice.nsw.gov.au/.

Your Statement of Claim must include the correct name and address of you (‘Plaintiff’) and the other party (‘Defendant’). If the Defendant is a registered company, you should ensure that the name and address on the Statement of Claim are the same as those on the ASIC register (see the ‘Who Can I sue?’ section of this information sheet). You should also include details of the claim such as any invoice number and when the debt became due. The Statement of Claim contains instructions on how to complete the form.

Once you have completed the Statement of Claim form you must file at least 4 copies of it with the court by handing the copies in to the court registry and paying the filing fee. One copy will be returned to you, two are for the Defendant and the other is retained by the Court.

You must then ensure the Statement of Claim is served on the Defendant. The Court has certain requirements for serving documents on a Defendant, so people often employ a process server to ensure that it is done correctly. You can also choose to serve the document yourself to try and reduce costs, although it is worth considering that people can react quite strongly to being served with court documents.

What can the other party (debtor) do?

Once the Defendant has been served with a Statement of Claim they have 28 days to either file a Notice of Defence (Notice of Defence Forms are available from the Local Court or on their website) or admit the Plaintiff’s claim and agree to repay the money. If the Defendant chooses to file a Notice of Defence it must be served on the Plaintiff no later than 14 days after it was filed with the Court.

If the Defendant fails to file a Notice of Defence with the Court or admit the claim and apply to repay the debt within the 28 days, the Plaintiff can apply for judgment by lodging a ’Notice of Motion for Default Judgment’, which is available from the Court or its website. If the Defendant does not have a good reason for failing to file a Notice of Defence, a default judgment application allows the Court to make a decision in the Plaintiff’s favour without going through the full trial process. This is only possible where the Statement of Claim sets out the Plaintiff’s case in enough detail, so you should ensure you complete it as best you can.

If the Defendant defends the claim, the matter will automatically be set down for a pre-trial review.

How much will it cost?

There is a small filing fee for the Statement of Claim. For further information on filing fees visit the NSW Law Courts website here: https://www.localcourt.nsw.gov.au/local-court/forms-and-fees/fee.html

Although each party can engage a solicitor to represent them, for many matters before the Small Claims Division there is no need for a solicitor and legal representation will usually significantly increase the cost of the proceedings. Generally, the successful party is not entitled to claim their legal costs from the other party, although they may be able to claim their administrative costs and expenses, such as service fees and witness expenses, for bringing or defending the claim.

Can I settle before the hearing?

Yes, the parties may settle the matter between themselves at any time before the hearing. They are encouraged to do so at the pre-trial review, and, during the pre-trial review, the Magistrate may refer the parties to a Community Justice Centre representative present at the Court. Community Justice Centres also offer mediation services.

The pre-trial review is an informal review of the facts of the dispute, and statistics show that an amicable settlement will often be reached at this stage. The review is conducted by an officer of the Court, usually a Magistrate. Failure by either party to attend the pre-trial conference without a good reason can result in an order being made against them.

What happens at the hearing?

If there is no agreement at the pre-trial review a hearing date is set. The person conducting the pre-trial review will advise all parties about the evidence they will have to present to ensure that a quick and fair trial will take place. Hearings are generally conducted by a Magistrate or an Assessor, and there should be minimal formality.

Enforcement

The order of the Magistrate made at the hearing is legally binding on the parties. If either party fails to comply with the order, it may be enforced against the defaulting party in the Local Court.

Northern Territory

In the Northern Territory, the Local Court can deal with debt recovery claims between $25,000 and $250,000. If the money that is owed exceeds $250,000 you must commence your action in the Supreme Court of the Northern Territory. If the claims are less than $25,000, they cannot be brought in the Local Court and must be brought in the Northern Territory Civil and Administrative Tribunal (NTCAT).

The limitation period for debt or contract issues is 3 years from the date on which the cause of action first accrues. The cause of action usually accrues when the debt becomes due or when the contract is not fulfilled. If you are outside the -year period you may still be able to bring a claim, but the other party can raise the expiration of the limitation period as a defence and NTCAT (or the court) may deny your claim.

Small claims procedure

In the Northern Territory, claims can be commenced in NTCAT or the Local Court depending on the size of your claim. For claims up to $25,000 your claim should be brought in NTCAT and for claims between $25,000 and $250,000 you should bring your action in the Local Court.

How do I make a claim?

NTCAT

You (the ‘Applicant’) should complete ‘Form 1 Initiating Application’ obtained from the NTCAT website. Make sure you carefully identify the party that owes you the debt (the ‘Respondent’). If you do not correctly identify the right entity that owes you the debt as the Respondent, any judgment that you receive may be unenforceable (see the ‘Who Can I Sue’ section of this information sheet).

When you have filed your initiating your Initiating Application with NTCAT and paid the applicable fee it will be assessed by the Registrar. If your Initiating Application is accepted, you will receive a copy to deliver (serve) to the Respondent.

Local Court

To start a claim, you must fill in a ‘Statement of Claim’ form, which you may obtain from any NT Local Court office or the Court’s website. Make sure you include accurate names and addresses for both yourself (‘Plaintiff’), and the other party (‘Defendant’). If you do not correctly identify the entity that owes you the debt as the Respondent, any judgment that you receive may be unenforceable (see the ‘Who Can I Sue’ section of this information sheet). You must also complete a ‘List of Documents’ form. Then hand in (file) three copies of the completed forms to the Local Court nearest to you. If, however, that venue doesn’t have a particular relationship to the Defendant or the claim, the Defendant can apply to have the matter transferred to another more appropriate venue of the Court.

The Statement of Claim and List of Documents must be delivered (served) to the Defendant personally, along with a ‘Notice of Defence’ (also available from a Local Court office or the Court’s website). This means that the documents must be delivered to the Defendant in person, and that mailing them is not sufficient. You can serve the Statement of Claim up to 6 months after the date it was filed, although this can be extended for another 6 months if you apply to the Court for an extension of time before the time limit has expired.

The Court can arrange service of the relevant documents to the Defendant. If you serve the documents yourself, you should prepare an ‘Affidavit of Service’ (a sample is provided on the Statement of Claim form). The Affidavit is proof that the Defendant has been served with the Statement of Claim. Depending on who the Defendant is, you may need to follow rules relating to service of documents set out in other legislation like the Business Names Act or Corporations Act. If you are unable to personally serve the Defendant with the documents, you may pay for a licensed process server or private bailiff to do this.

If you are claiming a sum of money, you may include a claim for interest on that amount. The Court may have discretion to award whatever rate of interest it chooses.

What can the other party (debtor) do?

NTCAT

The Respondent may be required to file a ‘Form 2 Response’ outlining the reasons why they oppose the application. If a response is filed, the Respondent will be required to serve the Applicant. A Respondent may also make a counterclaim against the Applicant by including it in the Form 2 Response.

Local Court

The Defendant has 28 days from the date on which the Statement of Claim is served to either settle the claim directly with the Plaintiff or file one of the following with the Court:

- a Notice of Defence along with a list of documents (if the Defendant intends to defend the claim);

- a Notice of Admission (admitting all or part of the claim); or

- an offer of compromise (e.g. An offer to pay by instalments).

A copy of any document filed by the Defendant will be sent to the Plaintiff.

If the Defendant wishes to bring their own claim against the Plaintiff (Counterclaim), they can do so by including the Counterclaim in the Notice of Defence.

If the Defendant fails to do any of these things within that time, the Plaintiff can apply for judgment without a court hearing by filing an ‘Application for Default Judgment’ form. This can be obtained from a Court office or its website. If the Defendant does not have a good reason for failing to file a Notice of Defence, a default judgment application allows the Court to make a decision in the Plaintiff’s favour without going through the full trial process. This is only possible where the Statement of Claim sets out the Plaintiff’s case in enough detail, so you should ensure you complete it as best you can.

The Defendant may, however, be able to apply to have the default judgement set aside and the matter re-heard in certain circumstances.

How much will it cost?

A small fee is payable for filing the Initiating Application/Statement of Claim with the relevant body. The fees are available at the NTCAT website and NT Courts website.

Can I settle before the hearing?

Yes, you may settle at any stage before or during the proceedings but before judgment, but you must let the Tribunal or Court know of the settlement once it has been finalised. You should not, however, tell the Court or Tribunal that a settlement offer has been made prior to it being accepted. If a settlement is reached you should, ideally, have a written and signed settlement agreement which you can file in court to prove the terms of the settlement.

What happens at the hearing?

NTCAT

In small claims matters, parties will usually represent themselves. It is only with the leave of NTCAT that they are entitled to be represented by a legal practitioner.

The tribunal member will manage the hearing and ensure that each party is given the opportunity to present their case and respond to the other party’s submissions. The Applicant will usually be asked to present their case first and the Respondent will then be given the opportunity to respond.

The NTCAT is not bound by rules of evidence and may inform itself of any matter relevant to a proceeding by any means it thinks appropriate.

Local Court

If you wish, you may have another person (eg. a lawyer, friend) represent you. If a lawyer represents you, it is up to you to pay their fees. If you are representing yourself be ready to prove your case. This means having all relevant papers with you (including any contracts, invoices, receipts, and diary notes) and arranging for any witnesses to attend the hearing.

The Court listens first to the Plaintiff’s case and then to the Defendant’s case. Note that the Court is also not bound by the rules of evidence. When the Court has heard the case in full it will give a judgment and make orders which must be obeyed by the party against whom the orders are made.

Costs

NTCAT

The usual rule in NTCAT proceedings is that the parties bear their own costs with the exception of certain unavoidable costs such as application fees which may be recovered.

Local Court

Costs may be awarded if the Court thinks it is reasonable to do so. All costs of the proceedings are awarded entirely at the discretion of the Court.

Enforcement

If the order is not obeyed, you can enforce the order. An NTCAT order can be registered and enforced by the Local Court and the Local Court can enforce its own orders. You may seek advice from the Court if you are in this position.

Queensland

In Queensland, the Magistrates Court can deal with debt recovery claims up to the value of $150,000. Debt recovery claims between $150,000 and $750,000 are dealt with by the District Court and debt recovery claims greater than $750,000 are dealt with by the Supreme Court.

The limitation period for debt or contract issues is 6 years from the date the cause of action arose. The cause of action usually accrues when the debt becomes due or when the contract is not fulfilled. If you are outside the 6-year period you may still be able to bring a claim, but the other party can raise the expiration of the limitation period as a defence and QCAT (or the court) may deny your claim.

Small claims procedure

Small claims are part of the minor civil disputes jurisdiction and are dealt with by the Queensland Civil and Administrative Tribunal (‘QCAT’). The Magistrates Court of Queensland does not have a small claims jurisdiction.

When can I use QCAT?

QCAT’s jurisdiction extends to:

- debt disputes – these involve disagreements with another person, business or company about a fixed or agreed sum of money, valued up to and including $25,000. Examples of a debt dispute include (https://www.qcat.qld.gov.au/matter-types/debt-disputes):

- unpaid invoices or accounts

- rent arrears, other than arrears of rent for a residential tenancy

- work done and/or goods supplied with the cost having been agreed beforehand

- money lent and not repaid

- IOUs

- dishonoured cheques;

- consumer and trader disputes – these involve disputes between a consumer and a trader, or between a trader and another trader, that arise out of a contract for the supply of goods and/or services and are valued up to and including $25,000 (or if the cost of rectifying any defect in the goods or services is within that amount) (see http://www.qcat.qld.gov.au/consumer-and-trader-disputes.htmhttp://www.qcat.qld.gov.au/minor-civil-disputes.htm for more information);

- property damage disputes – claims for payment of an amount for damage to property caused by, or arising out of the use of, a vehicle;

- residential tenancy disputes, including rooming accommodation disputes; and

- dividing fence disputes.

The maximum amount of money that can be claimed in QCAT’s minor civil dispute jurisdiction will be $25,000. If your dispute is about unpaid wages, then QCAT may not be the appropriate court even if the amount is less than $25,000. Such claims can be brought in one of the courts nominated under the Fair Work Act 2009. For more information see the Office of Industrial Relations information sheet on ‘Wage theft information for workers’’.

How do I make a claim?

To bring an action in QCAT for a minor debt dispute, you need to complete and file an ‘Application for minor civil dispute – minor debt’ using Form 03. To bring an action for a consumer and trader dispute, you need to complete and file an ‘Application for a minor civil dispute – consumer dispute’ using Form 01. You can obtain these forms and a free guide from QCAT on Level 9, Bank of Queensland Centre, 259 Queen Street Brisbane, from the local office of a Clerk of the Magistrates Court (who is also a Registrar of QCAT), from any Legal Aid Office, or from the QCAT website. The minor debt application can be completed online.

The claim form must include your full name and address as the person filing the claim form (referred to as the ‘Applicant’) and those of the other party (referred to as the ‘Respondent’) (see the ‘Who Can I sue?’ section of this information sheet). It should be lodged together with a copy of any relevant contract or other documents, such as receipts, which relate to the claim. You will have to provide multiple copies of these documents to QCAT: usually one for you, one for the Tribunal and one for each other party.

The Registrar of the Magistrates Court or the Registrar of QCAT can help you lodge your claim.

After your Application is filed, the Registrar of QCAT will return to you copies of your application and forms stamped with the QCAT seal. You must serve a copy of the stamped documents on the other party.

What can the other party (debtor) do?

If the Respondent is unable to attend the hearing, they may give their evidence in defence of the claim by filing a statement of oath or, with the consent of QCAT, they may appoint an agent to represent them. If the Respondent fails to do any of these things, the claim may be heard without them and a default judgment may be entered against them if requested. Sometimes, an application can be made for the matter to be re-heard.

In either case, if you are successful or if you have default judgment entered in your favour, you can apply for a warrant to recover the debt through, for example, compulsory deduction from wages or by seizing goods or property.

How much will it cost?

A small fee is payable when you lodge a claim. The amount of the fee depends on the amount claimed. This fee may be recoverable if you are successful. Application and appeal fees are listed on the QCAT website. In limited cases, you may be able to have the fee waived if you can demonstrate financial hardship.

Can I settle before the hearing?

Yes. If the matter is settled you should tell the Tribunal immediately and always confirm the settlement in writing.

The Tribunal or the principal registrar can also try and promote a settlement by referring the matter to mediation or to one or more compulsory conferences. The Tribunal or principal registrar can order a mediation to take place even if the parties do not consent.

A compulsory conference can also be used to identify the issues in dispute and the specific questions of fact and law to be decided. It is therefore essential to attend the conference, as the person presiding over it can decide to proceed in your absence and make adverse orders against you.

What happens at the QCAT hearing?

In QCAT proceedings, parties are not allowed to be represented by a lawyer unless the party is a child or a person with impaired capacity or both parties and the Member agree.

Both parties must organise documents required to support their case, such as contracts, bills for work done, sales slips, receipts, and photographs. Parties must also organise for their witnesses (who will assist in proving the facts of their case) to attend the hearing. Expert witnesses are called at a party’s own expense. Sworn written evidence can be used but verbal evidence is preferred.

The Member will usually ask if the parties can agree to settle. If an agreement is reached, it will be recorded by the Registrar; otherwise the Registrar will hear the dispute. It is then up to each party to the dispute to present their case and to call witnesses when necessary. After hearing both parties, the Referee will make a binding decision based on what they consider fair and equitable.

Costs

In QCAT proceedings, the parties must appear for themselves without representation and will usually bear their own costs. The Tribunal can order an unsuccessful Respondent to pay the Applicant’s costs if they consider it to be ‘in the interests of justice’, however the only costs recoverable are the filing and service fees. Legal representation costs are not recoverable.

If a party makes a settlement offer which the Tribunal considers reasonable and the other party rejects it, the Tribunal can order the other party to pay any costs incurred by the party that made the settlement offer after the offer was made.

Enforcement

Orders made by the Member are final and binding on all parties. Only in exceptional circumstances is an appeal against the decision allowed.

When an order for the payment of money is not satisfied, the other party may enforce the judgment in the Magistrates Court or by contacting the Civil Court Registrar at the courthouse who will give advice on enforcing the claim.

South Australia

In South Australia, the Magistrates Court can deal with minor claims up to the value of $12,000. If the money that is owed exceeds $12,000 and is less than $100,000, the Magistrates Court may still hear the claim but different procedures and fees apply. For claims in excess of $100,000, debt recovery is dealt with by either the District Court or the Supreme Court depending on the amount.

South Australia has the following limitation periods for different types of claims:

- personal injury – three years after the event (or six months after the event if you want to use the minor claims process)

- for a debt or contract issue – six years after the event,

- extensions may be granted by the court.

For debt or contract claims the cause of action usually accrues when the debt becomes due or when the contract is not fulfilled. If you are outside the 6-year period you may still be able to bring a claim, but the other party can raise the expiration of the limitation period as a defence and the court may deny your claim.

Minor claims procedure

In South Australia, small claims may be made in the Magistrates Court (in the Civil (Minor Claims) Division) (‘Court’).

When can I use the Court?

A claimant may use the Court for claims of up to $12,000 against defendants who provide goods or services, and against people and corporate bodies for debt or damages claims. Claims of between $12,001 and $100,000 may be dealt with in the Civil (General Claims) Division of the Court. Claims over $100,000 must be dealt with by the Supreme Court.

How do I make a claim?

Your first step before you officially commence bringing a claim should be to notify the Defendant of your intention. You can do this by completing and delivering to the Defendant a ‘Final Notice of Claim’ form or by sending a letter to the Defendant. If you skip this step, you cannot recover the costs of filing your claim against the Defendant if you are successful. You can purchase the final notice document online at https://online.courts.sa.gov.au or at the registry of any Magistrates Court in South Australia.

If you use a letter to tell the Defendant of your intended claim, you must also tell them:

- what is being claimed;

- the fact that they have 21 days to resolve the matter; and

- that, if the matter is not resolved, you intend to take the matter to the Magistrates Court.

It is also advisable to include information about the Defendant’s options, such as going to mediation. This letter does not have to be filed in court and can be sent directly to the Defendant.

If, after the 21-day period, there has either been no response or an unsatisfactory response, you can file the claim or agree to submit to mediation.

You can commence Court proceedings by completing a Claim form. This form contains instructions to assist you and is available from the Court, by either phoning 8204 2444 or online. If the claim is against a person, ensure that both of your names and the addresses are correct. If the claim is against an incorporated body, ensure that both the name and address on the form are the same as those on the company’s register. If you do not correctly identify the right entity that owes you the debt, any judgment that you receive may be unenforceable (see the ‘Who Can I Sue’ section of this information sheet).

You (‘Plaintiff’) must lodge your claim electronically via the online CourtSA portal and pay the filing fee. Once payment is finalised and approved the documents will be made available to you. You must deliver (‘serve’) one copy on the other party (‘Defendant’), and then complete an Affidavit of Proof of Service and file it in Court. Alternatively, you can pay a fee to have a sheriff’s officer serve the claim. All the forms that you need can be obtained from the Court. Unless the Court allows otherwise, the Claim form must be served within 6 months of filing it.

Don’t forget that you will not be entitled to the costs of filing a claim unless written notice of the intended claim (in either a written letter or a ‘Final Notice of Claim’ form available from the Magistrates Court) was given to the Defendant more than 21 days before your claim is filed.

What can the other party (debtor) do?

After the claim has been served, the Defendant has 28 days to either:

- settle the claim with the Plaintiff without going to court; or

- pay the full amount due; or

- file a Defence; or

- file a Defence and lodge a counterclaim.

If the Defendant files a Defence form, a copy will be sent to you by the Court, and (later) the Court will give you notice of the time and date of the hearing. If the Defendant does not settle or file a Defence within the specified period, you may ask the Registrar to make a default order against the Defendant without conducting a hearing. You can do this at any time from the end of the 28-day period. The Defendant can apply to the Court to set aside this default order.

How much will it cost?

A small filing fee is payable for all claim forms and must be paid when the completed Claim Form is filed at Court. As at 15 December 2020, the filing fee is $156. For more information see http://www.courts.sa.gov.au/ForLawyers/Pages/Magistrates-Court-Fees.aspx#civil .

Can I settle before the hearing?

Yes. Settlement can be achieved before any steps are taken by the Court. If this happens, the Plaintiff must advise the Court in writing.

The matter can be brought to an end by the parties by:

- by signing a formal agreement as to judgment and filing it with the court; or

- settling at the hearing.

Alternatively, the Defendant can:

- file an Admission of Liability document in court, in which the Defendant admits all or a part of the Plaintiff’s claim; or

- at any time before the hearing, pay an amount into court that the Defendant admits owing, plus an amount for the Plaintiff’s costs, for the Plaintiff to accept to settle the claim.

It is advisable (and sometimes necessary) that any terms of settlement are in writing.

The Court can also order the parties to attend a settlement conference or mediation to try and encourage the matter to settle.

What happens at the trial?

If there is no agreement before the hearing, the Court will send a notice of the date and place of a directions hearing to both parties. This is an informal Court appearance where the Court will enquire into how the case is progressing and attempt to help the parties to resolve the matter. If the matter is not resolved at the direction hearing, the Court will set the matter down for a final hearing.

At the final hearing Parties must present their cases logically, supported by any witnesses and evidence which the parties must have with them at the trial.

Both the Plaintiff and the Defendant are given a chance to present their side of the story. Lawyers are generally not allowed to appear for the parties, unless both parties agree or one party is a lawyer. The Defendant, Plaintiff and witnesses may be questioned by the Magistrate or the opposing party. The Magistrate will then make a decision that is legally binding on the parties.

The party who wins is normally entitled to ask the Magistrate to make an order that the losing party pay their court costs. Costs will usually include filing fees and witness fees.

Enforcement

If the Defendant does not pay the successful Plaintiff, the Plaintiff can approach the Magistrates Court to seek advice on a variety of enforcement actions.

Tasmania

In Tasmania, the Civil Court of the Magistrates Court can deal with debt recovery claims up to $5,000 as a minor civil claim, from $5,001 up to the value of $50,000 as a civil claim or, if the parties agree, an unlimited amount. For debts in excess of $50,000 where the parties have not agreed to use the Magistrates Court, you must commence action in the Supreme Court of Tasmania.

The limitation period for debt or contract issues is 6 years from the date on which the cause of action accrued. The cause of action usually accrues when the debt becomes due or when the contract is not fulfilled. If you are outside the 6-year period you may still be able to bring a claim, but the other party can raise the expiration of the limitation period as a defence and the court may deny your claim.

Small claims procedure

When can I use the Court?

If you are in dispute over a debt of $5,000 or less, you should bring your claim in the Minor Civil Claims Division of the Magistrates Court (‘Court’). The procedure discussed in this information sheet applies in the Minor Civil Claims Division.

How do I make a claim?

You will need to complete a Claim form and Notice to Defendant in which you give full and accurate details of the names and addresses of yourself (‘Claimant’), and the other party (‘Defendant’), and of your claim. If you do not correctly identify the right entity that owes you the debt, any judgment that you receive may be unenforceable (see the ‘Who Can I Sue’ section of this information sheet). It is preferable to file your claim in the Registry that is closest to the district in which your claim arose. You must file 3 copies of your claim (and the original). The Court will retain the original and stamp the other three copies. One copy is for the Defendant, another for you to keep and the last for the Affidavit of Service. One stamped copy must be ‘served’ on the Defendant. You can either do that yourself, arrange for a process server to do so., or the Court will serve it for you. You have one year after filing your claim to have it served on the Defendant. If you require longer, you must seek the permission of the Court. If you arranged the service, you then need to file an Affidavit of Service at the Court to prove the Defendant has received the claim.

Copies of a claim form, Affidavit of Service and other relevant court forms can be obtained from the Court registry or online.

What can the other party (debtor) do?

Once the Defendant is served, the Defendant has 21 days to:

- pay the amount claimed;

- settle the matter; or

- file a defence and, if appropriate, a counter claim.

If the Defendant files a defence within that time, you will receive a copy and the Court will fix a date for a directions hearing. If the Defendant does not, and the matter is not settled, you may apply to the Court for default judgment.

How much will it cost?

A small filing fee is payable when you lodge your claim. As at 18 September 2020, the filing fee is $121.50. There is also a service fee payable for the delivery (service) of the claim to the Defendant. (Check the Magistrates Court website for further details.) Alternatively, you can arrange for the claim to be served yourself.

Can I settle before the hearing?

Yes, although if you settle the dispute before the hearing you should advise the Registrar in writing that you wish to withdraw your claim. It is also advisable to confirm any terms of settlement by making an application to the Court for a Consent Order. The Consent Order form and instructions on the preparation of it are available from the Court or its website.

What happens at the hearing?

Generally, neither party may be represented by a lawyer at the hearing unless both parties agree and permission is granted by the Magistrate. You will need to have given copies of all relevant documents that you intend to rely on to the other party and to the Court.

At a directions hearing, the Magistrate will enquire into the progress of the action and explore ways of achieving a settlement. If settlement is not achieved, the Magistrate will set a date for mediation or set a date for the hearing.

At the hearing you will be able to tell the Magistrate what happened and what the basis of your claim is. You will be expected to make your statement under oath. You should show the Magistrate any evidence that supports your claim. After you have presented your case, the Magistrate will give the Defendant and their witnesses an opportunity to tell their side of the story. The Magistrate will encourage the parties to settle. If this is not possible, the Magistrate will decide the case. For more detailed information about the Court process, obtain the minor claims information brochure from the Court Registry or online.

The Magistrate’s decision is final and binding, with limited provision for appeal. The costs of filing the claim may be awarded if you are successful but generally other preparation costs are not.

Enforcement

If an order of the Magistrate for the payment of money is not complied with, the party in whose favour the order was made can enforce the judgment by returning to the Magistrates Court.

Victoria

In Victoria, the Magistrates Court can deal with debt recovery claims up to the value of $100,000. Debt recovery claims above $100,000 can be brought in the County Court or the Supreme Court.

The limitation period for debt or contract issues is 6 years from the date on which the cause of action accrued. The cause of action usually accrues when the debt becomes due or when the contract is not fulfilled. If you are outside the 6-year period you may still be able to bring a claim, but the other party can raise the expiration of the limitation period as a defence and the court may deny your claim.

Small claims procedure

In Victoria, small claims can be commenced in the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (VCAT) or in your local Magistrates’ Court.

When can I use VCAT?

VCAT is intended to offer a low cost, accessible, efficient alternative to the Magistrates Court and other courts. Often the VCAT will deliver its decision on-the-spot or shortly after hearing.

If your claim is a “consumer and trader dispute” arising under the Australian Consumer Law and Fair Trading Act 2012 (Vic) (ACLFTA) and is a claim for no more than $15,000, it is considered a ‘small claim’ and may be heard in the Civil Claims List of VCAT as a ‘small claim’.

A consumer and trader dispute is one ‘arising between a purchaser or possible purchaser of goods or services and a supplier or possible supplier of goods or services in relation to a supply or possible supply of goods or services’. Examples of such claims are disputes about items purchased that won’t perform, services you paid for that are inadequate or late, not being paid for services or goods that you supplied and misleading or deceptive conduct, false representation and unconscionable conduct in business. We consider that freelance editors should be able to go to VCAT to recover debts owed to them under contracts for their services, because they fall within the broad definition of ‘consumer and trader disputes’.

VCAT will not hear disputes about services provided under purely private arrangements as distinct from those in trade or commerce, personal injury disputes, disputes between people who are not connected with Victoria or disputes not arising under a contract.

In ‘small claims’ matters, the parties cannot be represented by lawyers unless the Tribunal is satisfied that the other party will not be unfairly disadvantaged and, even then, the Tribunal will usually not make orders for costs. In other words, even if unsuccessful, a party will not usually be required to pay the costs of the successful party. VCAT is located in Melbourne but also sits at a number of metropolitan and country locations on a regular basis.

Local Magistrates’ Court

Alternatively, a debt recovery action can be commenced in your local Magistrates’ Court. If your claim doesn’t fall within the specific categories of dispute eligible for hearing by the VCAT or you are outside the Melbourne metropolitan area, you can consider the Magistrates’ Court. More information on the Victorian Magistrates’ Court, including court costs and locations, may be found on the website https://www.mcv.vic.gov.au.

Unlike other States, there is no small claims division within the Victorian Magistrates’ Court. The Magistrates’ Court hears claims of up to $100,000 in its civil jurisdiction. Generally, claims must be brought within 6 years of the date the dispute arose.

If an action in a consumer and trader dispute is commenced against you in the Magistrates’ Court, you can ask the court to transfer your case to VCAT. The court may agree that it would be more appropriately heard by VCAT.

If you are the purchaser in a consumer and trader dispute and the claim against you is for $15,000 or less, you also have the option of paying the amount being claimed from you to the VCAT for it to hold and then your action will automatically be dismissed from the Magistrates’ Court and transferred to VCAT. You can only do this before the case has commenced hearing.

How do I make a claim?

VCAT

You (the ‘Applicant’) should obtain an ‘Application to Civil Claims List’ form by calling the VCAT Civil Claims List Registry on (03) 9628 9830 or 1800 133 055 outside the Melbourne metropolitan area. The application form can also be obtained from, or submitted via, the VCAT website: www.vcat.vic.gov.au. Fill in the application form and send it off to VCAT with the appropriate fee. Once received, the Registrar will send a copy of your application to the other party (the ‘Respondent’). Shortly thereafter, you will be notified of the time, date and place for the hearing of your claim. It is important to read the notice carefully to determine the type of proceeding that will take place.

VCAT may refer your claim to alternative dispute resolution ‘ADR’. If the amount of the dispute is between $500 and $5000, the dispute may be suitable for “fast track mediation”. This means that a mediator from the Dispute Settlement Centre of Victoria will assist to resolve the dispute.

The Magistrates’ Court

Obtain a copy of a Claim Form (the ‘Complaint’) from the Court or from the Court website. To find your closest Magistrates’ Court, telephone the Civil Division Registry on (03) 9628 7777 or go to the website. You should also review information on completing a Complaint and starting a civil matter on the Court’s website.

You (the ‘Plaintiff’) must set out your claim in the Complaint. You will probably need legal assistance to draft it. However, some Court Registrars are willing to provide general assistance as to how to set out your claim. You must also complete an ‘Overarching Obligation Certification’ form and ‘Proper Basis Certification’ form – both can be obtained from the Court website. Once these forms are drafted, you need to make a photocopy of the Complaint and deliver the original Complaint with the other two forms to the court registry along with the appropriate fee. This is called “filing”.

You will then need to ‘serve’ (ie. deliver) a copy of the Complaint, stamped by the Court Registrar, on the other party (the ‘Defendant’), along with the two copies of the blank ‘Notice of Defence’ form. The ‘Notice of Defence’ form can be found on the Court website.

Once the documents have been served, you must complete an affidavit of service and swear or affirm it in the presence of an authorised person. If you like, you can pay a process server to serve the documents for you and then they will complete the affidavit of service.

What can the other party (debtor) do?

VCAT

The Respondent is not required to lodge any form with the VCAT in order to defend your claim. The Respondent can simply attend the Tribunal on the date set for the hearing with their evidence. However, the Respondent is entitled to bring a Counterclaim against you by also completing and filing the ‘Application to Civil Claims List’ form.

The Respondent may also choose to settle or pay the amount claimed at any time before the hearing. The parties are encouraged to settle their dispute before the hearing. To help settle disputes, the VCAT can arrange for appropriate cases to be mediated. If a dispute is settled between the parties, the Applicant must notify the Registrar of this in writing and request that the claim be withdrawn. The Applicant must then notify all other parties in writing of the withdrawal. If a dispute is settled at mediation, the Mediator will encourage the parties to make a written record of their settlement terms. The VCAT may make orders necessary to give effect to the settlement reached by the parties.

If you wish to withdraw your application, you must give written notification to VCAT and all other parties involved immediately. Failure to do so may result in costs being awarded against you.

Alternatively, the Respondent may seek to adjourn the hearing, in which case the Respondent will need to forward supporting documents such as medical certificates and, usually, the written consent of all other parties to the VCAT prior to the hearing date.

If no adjournment is granted and either party fails to attend the hearing, the hearing will usually proceed without them. It is very difficult to obtain a re-hearing.

The Magistrates’ Court

Once the Defendant has been served with the Complaint, they have 21 days from the date of service to either pay you or defend the claim by filing a ‘Notice of Defence’.

The Defendant may also lodge a counterclaim in the same proceedings. This has the effect of the Defendant in the first hearing becoming the plaintiff in the second hearing and the Plaintiff in the first hearing becoming the defendant in the second hearing. A counterclaim is normally heard at the same time as the hearing of the original claim unless the Court otherwise orders.

If the Defendant defends the claim, they need to lodge a completed ‘Notice of Defence’ form with the Court and serve a copy on you, the Plaintiff. If the Defendant fails to do this within the 21 days, you should apply to the Court for a default judgment against the Defendant by filing an ‘Application for order in default of defence’ form, which is available from the Court or on the Court website. You also need to have filed an affidavit of service of the Complaint with the Court to obtain judgment in this way.

Once the Notice of Defence has been filed, the Court will usually set the matter down for a pre-hearing conference within two months. A pre-hearing conference is an informal conference between the parties and the Registrar of the Court to clarify the issues in dispute and promote a settlement or, alternatively, to ensure that the matter is ready for hearing.

The parties are encouraged to settle their dispute before the hearing. If this happens the parties must notify the Court in writing that the dispute has been settled and request that the claim be withdrawn by filing a ‘Notice of Discontinuance’.

Whilst mediation is no longer part of the formal Court process, parties may pursue mediation for themselves, independently of the Court. A dispute can only be referred to mediation if both parties agree. The Dispute Settlement Centre conducts mediations for free. They can be contacted on (03) 9603 8370 or 1800 658 528 (toll-free).

If the dispute is not settled at the pre-hearing conference or by mediation, and the amount claimed is less than $1,000, the Court will usually set the matter down for arbitration. Arbitration is an informal court hearing conducted by a magistrate. A decision by the Court in arbitration has the same effect as if it were made at an ordinary hearing.

How much will it cost?

VCAT

In most cases there is a filing fee to commence legal proceedings. The filing fee in the VCAT varies depending on the amount you are claiming. As at 15 December 2020, for claims between $1 – $3,000 the amount is a $65.30 ‘standard’ fee, $93.30 ‘corporate’ fee or no fee for concession card holders. For claims between $3,001 – $15,000 the amount is a $217.70 ‘standard’ fee, $311 ‘corporate’ fee or no fee for concession card holders. Additionally, you can apply for a fee waiver by completing and lodging a fee waiver form. The principal registrar decides whether a fee is waived. Please refer to the website for more information about fees in the VCAT.

The Magistrates’ Court

In the Magistrates’ Court, filing fees are also relative to the amount claimed. As at 15 December 2020, claims between $1 – $1000 have a filing fee of $151.10, claims between $1001 – $10,000 have a filing fee of $315.50, claims between $10,001 – $40,000 have a filing fee of $479.80, and for claims over $40,000 there is a filing fee of $719.80. There are additional fees if you ask the Court to arrange for service on the Defendant. Unlike in the VCAT, a successful Plaintiff can usually apply to the Court for a costs order against the Defendant.

What happens at the hearing?

VCAT

For claims where less than $15,000 is in dispute, parties are generally not allowed to be represented by a lawyer and must prepare their cases to the best of their ability. The parties must take to the hearing all of the evidence, including relevant original documents (such as contracts, receipts, cheque books, time sheets, written quotes, photographs) and witnesses. If an interpreter is required, the VCAT should be contacted. Interpreters can be arranged by the VCAT at no cost.

First the Applicant, then the Respondent, presents their case to a Tribunal Member in a fairly informal atmosphere. Any other party with ‘sufficient interest’, (for example, persons who have carried out work or supplied goods in connection with the contract) will then give evidence. Evidence is given under oath. The Tribunal Member can ask questions at any time. Both parties are given the opportunity to question each other. The Tribunal Member will attempt to bring the parties together to settle the dispute. If this is not possible, the Tribunal Member will make an order.

The VCAT must give reasons for a decision, however these are not always written. If the VCAT gives oral reasons, a party may, within 14 days, request that the VCAT provides written reasons.

The Magistrates’ Court

Parties may be represented by a lawyer. A Pre-Hearing Conference may be scheduled after the lodging a notice of defence. At the Conference, a Registrar will try and assist the parties in reaching an agreement to resolve the dispute. If the dispute cannot be resolved an attempt will be made to identify the issues in dispute. If the matter is still not resolved, it will be listed for a final hearing before a Magistrate.

Following a Pre-Hearing Conference, a hearing date will be set. The hearing is conducted before a Magistrate according to the rules of the Court. After hearing both parties, the Magistrate will hand down a judgment and may make an order as to costs (the legal costs of making or defending the claim) against the losing party.

Costs

VCAT

Generally the costs involved in a proceeding cannot be recovered from the other party even if you are successful, although VCAT does have discretion to award costs if it is satisfied that it is fair to do so. This may be done where one party has conducted the proceedings in a way that disadvantaged the other party or unnecessarily prolonged the proceedings.

Where one party makes a settlement offer that is rejected by the other party and VCAT considers that the offer was fair and no less favourable to the other party than the ultimate outcome of the proceedings, the party that made the offer is entitled to recover any costs they incurred after the offer was made from the party that rejected the offer.

VCAT can also make orders that an unsuccessful party must reimburse the other party for fees that they have paid in the proceedings.

The Magistrates’ Court

The Court has full discretion to determine who must pay costs and the extent of the costs to be paid. Costs are usually assessed by the Court according to a ‘scale’ which determines the appropriate amounts that can be awarded.

Where one party withdraws their claim (or part of it) or it is dismissed by the Court, they must pay the other party for the costs associated with it.

Similarly to VCAT, where a Plaintiff makes a settlement offer that is rejected by the Defendant and the Plaintiff ultimately obtains an order which is no less favourable to the Plaintiff than the offer, the Defendant must pay the Plaintiff’s costs incurred after the offer was made.

Enforcement

VCAT

An order by a Tribunal Member is legally binding. If an order for payment of money is not complied with, it can be enforced in the Magistrates’ Court.

The Magistrates’ Court

An order by the Magistrate is legally binding. If a party does not pay in accordance with the Magistrate’s order, the order can be enforced in the Magistrates’ Court.

Appealing the Decision

VCAT

A party may seek leave to appeal a decision of the VCAT to the Supreme Court of Victoria on questions of law. Be aware that time restrictions apply.

The Magistrates’ Court

A review of the decision of the Magistrate may be made in certain circumstances by the Supreme Court of Victoria but again be aware that time restrictions will apply.

Alternatives to Legal Proceedings

Mediation

In both VCAT and the Magistrates’ Court the parties are encouraged to settle their dispute outside the formal system. VCAT also have an Alternative Dispute Resolution service which is provided free of charge. If the dispute is not settled it proceeds to a hearing on the same day.

Under the ACLFTA the Director of Consumer Affairs Victoria can order parties to mediate or conciliate their dispute. This is where the dispute is between a business and a purchaser, or a consumer and a supplier of goods or services in trade and commerce. This aims to assist small businesses in resolving their disputes. Parties may also pursue mediation for themselves independently of the court, provided both parties agree to the process. The Dispute Settlement Centre of Victoria conducts mediation for free and offers a free dispute advisory service. They can be contacted on 1300 372 888 for Melbourne enquiries or go to their website via https://www.disputes.vic.gov.au/.

Western Australia

In Western Australia, the Magistrates Court can deal with debt recovery claims up to the value of $75,000. If the money that is owed exceeds $75,000 but is less than $750,000 you must commence action in the District Court of Western Australia. Any amount over $750,000 must be commenced in the Supreme Court.

The limitation period for debt or contract issues is 6 years since the cause of action accrued. The cause of action usually accrues when the debt becomes due or when the contract is not fulfilled. If you are outside the 6-year period you may still be able to bring a claim, but the other party can raise the expiration of the limitation period as a defence and the court may deny your claim.

Small claims procedure

The Magistrates Court deals with criminal matters and civil matters and consumer/trader claims for debts, including:

- claims for debts up to $10,000 (known as a Minor claim);

- claims for debts up to $75,000 (known as a General Procedure claim);

- consumer/trader claims over the sale, supply or hire of goods or services up to $75,000;

- residential tenancy agreement claims to enforce certain conditions of the agreement or to claim monies under the agreement up to $10,000; and

- claims by property owners to recover possession of real property, which is not subject to an agreement under the Residential Tenancies Act 1987, where the amount of gross annual rental value is less than $75,000.

How do I make a claim?

Obtain a claim form from the Magistrates Court together with a copy of any printed brochures and information booklets (available online from the Magistrates Court website). The relevant forms and information are also available online at the website for the WA Courts Service.

To make a Minor claim you will need to complete the Minor Case Claim Form 4 and pay the prescribed fee (for claims less than $10,000). You may lodge the claim online if you have a credit card or the completed form together with the application fee in person at the court registry.

Once you (the ‘Plaintiff’) have lodged your claim at the court you will need to ‘serve’ it on the other party (the ‘Defendant’). This means giving your claim to the Defendant. There are special rules for serving a claim. The claim has to be served as soon as practicable, and within one year after the day on which you lodge it. You may serve the claim yourself, such as handing the claim to the individual, their lawyer, or a person authorised in writing to receive documents for the individual, or by paying an additional fee for an enforcement officer, such as a bailiff, to serve the claim.

When you complete your claim form you can also complete a Statement of Claim, which narrows the issues in dispute and reveals your case. If you do not lodge a Statement of Claim at this time you can lodge one within 14 days of receiving a notice of intention to defend from the Defendant or after a pre-trial conference. Get legal advice about what should be in your Statement of Claim.

In some circumstances you may name more than one defendant on the claim. This is called joining defendants. Joining defendants may be done when a claim is issued or at a later date. Legal advice should always be sought before joining defendants.

How much will it cost?

A small fee is payable when you lodge your claim. As of 15 December 2020, the filing fee for a minor claim against an individual debtor is $156.20 or $302.20 if the Defendant is not an individual (such as a company). For more information see the Magistrates Court website.

Interest may also be claimed from the date the claim arose. Write on the claim that you are claiming interest.

In a Minor claim, you are not expected to comply with the ‘rules of evidence’ and legal representation is not allowed unless all parties and the Magistrate agree. Usually each person must pay their own lawyer’s fees.

What happens next?

The Defendant is required to respond to the claim within 14 days if served within Western Australia or 21 days if service is within another State or Territory of Australia from the date they are served by either:

- admitting the debt;

- disputing the debt; or

- admitting part of the debt and defending the balance.

If there is no response from the Defendant, judgment will be made in the Plaintiff’s favour.

Where the Defendant disputes part or all of the debt, the Defendant will be required to lodge a notice of intention to defend. Then the parties will be brought together for a pre-trial conference which will be conducted by a registrar of the court. The parties are encouraged to further clarify the issues and to settle the matter. If the matter is not settled, the registrar will either list the case for trial or a listings conference in front of a Magistrate of the court.

For a Minor Case claim, both parties can elect to have access to a less formal dispute resolution process. This saves both parties time and money.

Can I settle before the hearing?

Yes. If the matter is settled, you should advise the Magistrates Court in writing that you wish to withdraw your claim. If the Defendant admits to only part of the claim, get legal advice before accepting an offer to settle in this situation.

What happens at the trial?

A lawyer cannot represent parties to a Minor Claim unless all parties agree, or the court grants special permission for you to have a lawyer. In any event, for Minor Claims the lawyer’s costs are generally not recoverable even if you win your case, unless the court is satisfied that exceptional circumstances exist.

Each party presents their case before the Magistrate. Evidence is given under oath. Each party is then given the opportunity to ask questions and cross examine the other party’s witnesses. Each party then summarises their case and the Magistrate will make a decision.

As the Claimant, you will usually be the party who begins the proceedings by making an opening address and outlining your claim to the Court. Following this, you will be able to give evidence in support of your claim and call witnesses. The Defendant can cross-examine your witnesses after you have called them (you will then have the same opportunity if the Defendant calls any witnesses). This concludes the stage where you present evidence and the Defendant will begin their case. They will have an opening address and can present evidence and call witnesses. After the Defendant has finished, you will make your final address to the Court and persuade the Court that your case should succeed. The Defendant can then explain to the court why your claim should not succeed.

If the Defendant fails to attend the trial, you may be able to proceed with your case if the Defendant has been notified of the trial dates but fails to attend. If the defendant does not lodge a response within the time stated on the claim, you may apply for a default judgment. An application for default judgment must be made within 12 months of the date the claim was served on the defendant.

Enforcement

If you are successful and the Defendant does not make an acceptable proposal to pay the debt and costs to you there are a number of methods of enforcement. Firstly, a Means Inquiry may be conducted before the court to determine whether the Defendant (also referred to as the judgment debtor) has the ability to pay, and whether it is more appropriate that the debt be paid in full or by periodic instalments. Secondly, the court may also order a Property (Seizure & Sale) Order for the sheriff or bailiff to seize and sell the judgment debtor’s property to satisfy the debt owed to you. Thirdly, the Court can make a Debt Appropriation Order which requires a person who will or does owe money to the Defendant to pay that money to you directly. If the Court makes an instalment order and the debtor does not pay, the Court can make an ‘earnings appropriation order’ requiring the debtor’s employer to pay part of the debtor’s salary to you instead.

Enforcement orders are applied by completing Form 6 Application or Request to a Court with the prescribed application fee. An application for an enforcement order must be made within 12 years from when judgment was given.

Appeal

For minor cases not decided by a Magistrate you can appeal to a Magistrate in the Magistrates Court against the judgment on limited grounds. If it was a general procedure claim or a minor claim decided by a Magistrate you can appeal to the District Court, but the appeal must be commenced within 21 days after the date of judgment in the Magistrates Court.

If the 21 days has passed, you will have to seek leave to appeal via the District Court’s Form 6 Appeal notice and serve an affidavit in support along with appeal papers.