Revealing Beauty from Bones: Interview with artist Gerard Geer

Moon Orchid by Gerard Geer. Photograph by Ellen Duffy ellenduffy.com

Gerard Geer is a Melbourne based sculptural artist with an insatiable curiosity for the anatomical inner workings of all things organic. Predominately using animal bones as his medium, his work combines skeletal articulation, chemistry, and fantasy to create intricately articulated works that conjure a slightly distorted reflection of nature. Through this process he breathes new life into the medium he works with, to create pieces that explore ideas of impermanence, mortality and rebirth.

Gerard came to Arts Law as a client in 2013 when he had unknowingly broken the laws around making artwork using animal and plant products in Australia. We recently caught up with Gerard to chat with him about his experience ahead of his new exhibition at beinArt Gallery, Luminosity & Dust.

Arts Law: Animal materials, particularly, bones, skulls and feathers seem to form a really central part of the artworks that you make, what sparked your interest in this type of art making? Why are these materials so important to you and your artistic practice?

Gerard Geer: Ever since I was a kid I have been fascinated with animal bones. The bones make up the scaffolding of our internal organic machinery, and as a curious kid wanting to know how things ‘worked’ I would collect bones and spend hours looking at and playing with them to try to deepen my understandings.

I first started to make artworks out of animal bones around 10 years ago, after a ringtail possum that my family had raised was killed by a neighbourhood cat. Her name was Jasmine, and we had rescued her from her mothers pouch from the side of the road. Her mother had been hit by a car. I wanted to make something beautiful using the bones that were left behind, as my way of cherishing her memory, and this became a strong influence in my creative drive.

Over the next few years I would pick up roadkill wherever I found it, wanting to take something that was either disregarded or viewed as trash, and transform it into something new and beautiful. I felt that using animal bones as a medium for artworks challenged that perception that an animals’ body was something to look away from, while also highlighting the impact that we as humans have on our environment and the animals we share the earth with.

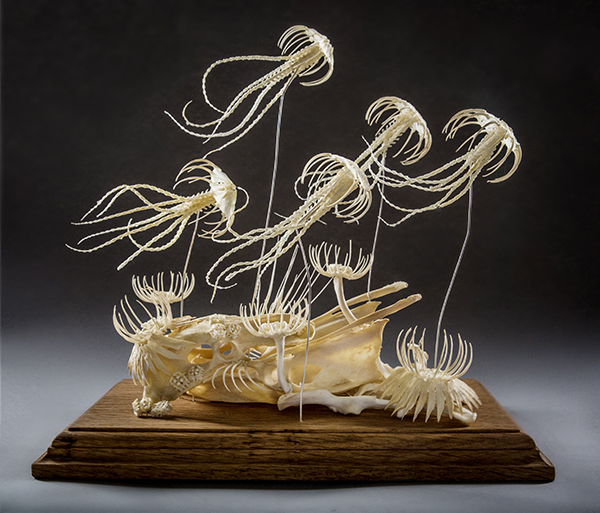

Jelly Swarm by Gerard Geer. Photograph by Ellen Duffy ellenduffy.com

AL: Is it significant to you that these materials are found not purchased?

GG: When I first starting working with animal remains I would only work with animals that had died of natural causes or human impact. Most of my medium was sourced from roadkill or peoples pets which were donated to me, but I had preferred to use the remains of animals I had found myself. Knowing where they were from and the condition I had found them in were all an integral part of the story that my finished pieces told.

AL: So, when we last spoke to you in 2013, you had just been informed that you have inadvertently committed offences under the Wildlife Act in Victoria; how did you initially find out that your work was illegal?

GG: Through sharing my work on social media, I found that there were a number of people around the world who were interested in the artwork I had been making. When a prospective buyer enquired about one of my pieces, I made a few phone calls to find out whether there were any bio-security issues with sending animal remains internationally. I was eventually put in contact with the then Department of Sustainability and Environment (now Department of Environment and Primary Industries), who informed me that I would not be able to send native Australian animal remains internationally without a permit.

A few weeks later I was visited at home by two members of the DEPI who came with printed out images of artworks I had published online, along with the statements about each piece that I had written detailing what the bones I had used were and where they had been found.

The DEPI officers explained to me the offences I had unknowingly committed, and outlined the penalties of committing those offences. They understood that I was unaware of the laws, and had not intended to have broken them, and with this in mind they advised me that I would not be punished under the act if I were to immediately destroy the artworks I had made using native animal remains, and any native remains in my possession.

Lorifox Avisaur by Gerard Geer, one of the works involved in the 2013 controversy. Photograph by James Mauger jamesmauger.com

AL: That must have been devastating to learn that you would potentially have to destroy years and years of work, do you remember how that felt at the time?

GG: I remember it vividly. I was absolutely heartbroken, to learn that I had to destroy these artworks that I shared a deep emotional connection to, felt love for. Having created these artworks as an attempt to create a beautiful new life for something that was cut so short was agonising.

Not wanting to have to destroy my works, I wanted to fight to save them as much as I could, and to be able to continue working with found animal remains as a medium. A close friend of mine’s mother recommended that I contact Arts Law Centre of Australia. She is an artist herself, and had received assistance from them in the past. We had hoped that perhaps there might be a way to change the laws to allow for creative artists to legally obtain native remains for use in artworks.

AL: In an article written at the time you mentioned that you were planning one last show before destroying the works, did you end up having the show? And what was the result of your interactions with the Victorian Department of Environment and Primary Industries? Were you charged or ordered to destroy your work?

GG: Thankfully I didn’t wind up having to destroy my work. Around two or three weeks after the initial visit I was contacted by the DEPI and told that a small exception would be made for my works. I was allowed to keep the specimens I had already collected and processed, and the artworks I had made, but would be bound to the conditions of the Wildlife Act. This meant that I could no longer collect roadkill. I was given a permit to keep what I already had, and would be able to continue working with animal remains provided that they were obtained lawfully under the wildlife act. I would also be bound to the conditions of the wildlife act, which involves applying for additional permits if I want to display my artwork outside of the premises listed on my permit. Also anyone who might buy my artwork would need to have a Wildlife Specimen License.

AL: We’re very happy to see that you’re still making work, in fact you have a show on now! Do you feel your experience in 2013 has impacted on your artistic practice, conceptually and practically in terms of the animals that you choose?

GG: After the events of 2013, it took me over a year before I was able to continue making art. Having had a big part of the ethos of my work rendered inaccessible, I needed to take some time to revaluate what I was doing and what it was that inspired me.

The shift from using native animals to non-native animals is very visible in my work. Sharing a spiritual connection with native animals, I found it difficult to translate those same ideas and feelings into works utilising non-native animals. Initially I became very methodical with my work, and spent time developing my naturalistic anatomical understanding and skills. This process led me to begin working with smaller and smaller specimens, and developing more intricacy in my pieces.

AL: Do you think this experience with the law made you more risk adverse or more aware of the intersection between the law and art?

GG: In this particular field, absolutely. I have realised that it is just too difficult to legally work with native animal specimens. While I initially felt that this was something that should be changed, I now recognise that while the laws are difficult to navigate and harsh if they are not adhered to, that they are there for good reason. I do however feel that the laws should be homogenised to an extent across the different states to make the whole process somewhat simpler to understand.

It is difficult though, because I don’t feel it is the place of art or artists to follow the law without question. More so, it is our place to hold up a mirror to reflect the things we see in the world in a new light and context, to ask questions and challenge acceptance.

In this context though, having taken the time to understand why these particular laws are in place, I feel that the reasoning behind why the Wildlife Act was written is more important than my particular creative expression. A change in the laws along the lines I had initially proposed could potentially open up loopholes for those willing to exploit native wildlife, and this is not something I could justify.

Winter by Gerard Geer. Photograph by Ellen Duffy ellenduffy.com

AL: We also notice you have been conducting Skeletal Articulation workshops in Melbourne- are people receptive/interested in the idea of marking art from animal materials?

GG: The skeletal articulation classes have been fantastic! I will be running our second class next weekend (the 30th-31st of July), and I am very excited. I was amazed that not only did the first class sell out, but all of the participants were women. Which is a trend I’ve noticed over the last few years, that the revival of taxidermy and its associated art forms has been predominantly a female-driven movement.

The success of the classes has shown me that there are many people out there who share the love that I have for anatomy, and share the same passion and respect for animals. The focus of the class in on the processes of preparation, cleaning and naturalistic articulation, and for the class I am teaching how to prepare a mouse specimen. So far, two students have replicated the entire process I am teaching, and I am expecting to see more over the next few weeks.

The interest in the classes, as well as the interest in my artworks, tells me that people are definitely interested in the idea of using animal materials as art. But I think that my favorite thing about the interest is the way that it makes people ask questions. When people question if the animal specimens are obtained ethically, it opens a dialogue about the way that we use and the impact we have on animals and the greater environment around us. *You can find the details of Gerard’s classes at his facebook page here.

AL: What’s your advice to someone who is starting out in this practice of making art using animal and/or plant products?

GG: My advice to anyone wanting to work with animal and plant products would be to familiarise yourself with the laws in your state surrounding the mediums you are wanting to work with before you start working with them. The difficulty with these laws is that they aren’t Australia wide, and actually vary quite dramatically state by state. In some states you can apply for permits to collect roadkill, and can legally possess or sell it. However as different states have different laws, someone interested in buying your artwork may be in a state that has laws that make the acquisition of native animal specimens very difficult. These problems can become substantially greater if you look at exporting artworks to international countries, as laws and regulations become even more complex. It is just easier to avoid working with native animal specimens entirely.

Thank you to Arts Law interns, Phoebe Boyle from University of New South Wales for her assistance with this interview as well as preparing the information sheets and Carrick Brough from Queensland University of Technology for his assistance in preparing the information sheets.